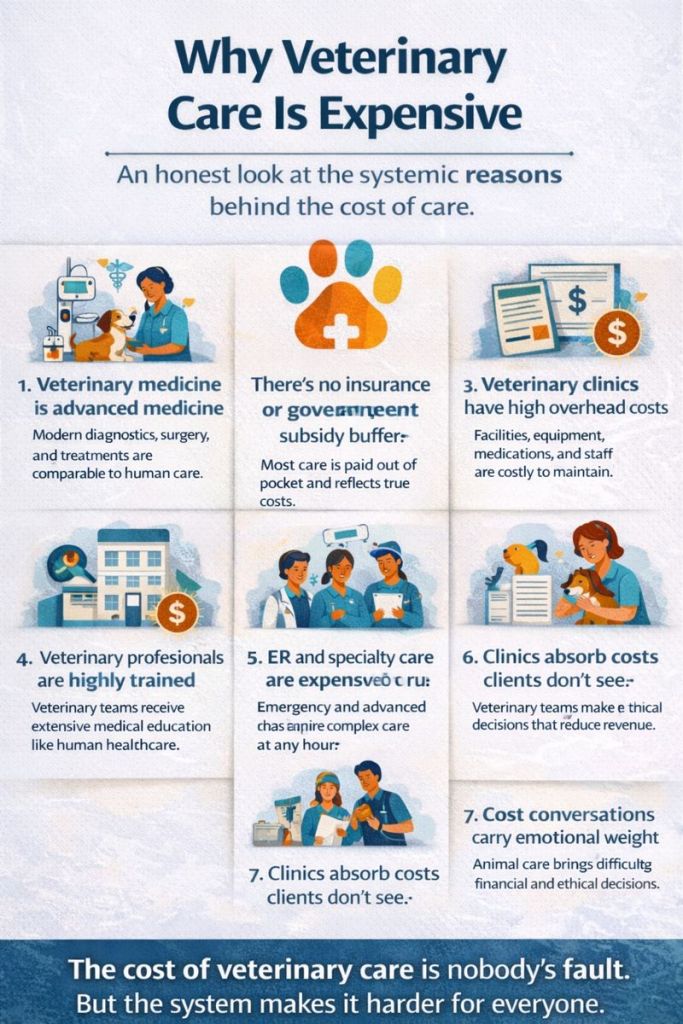

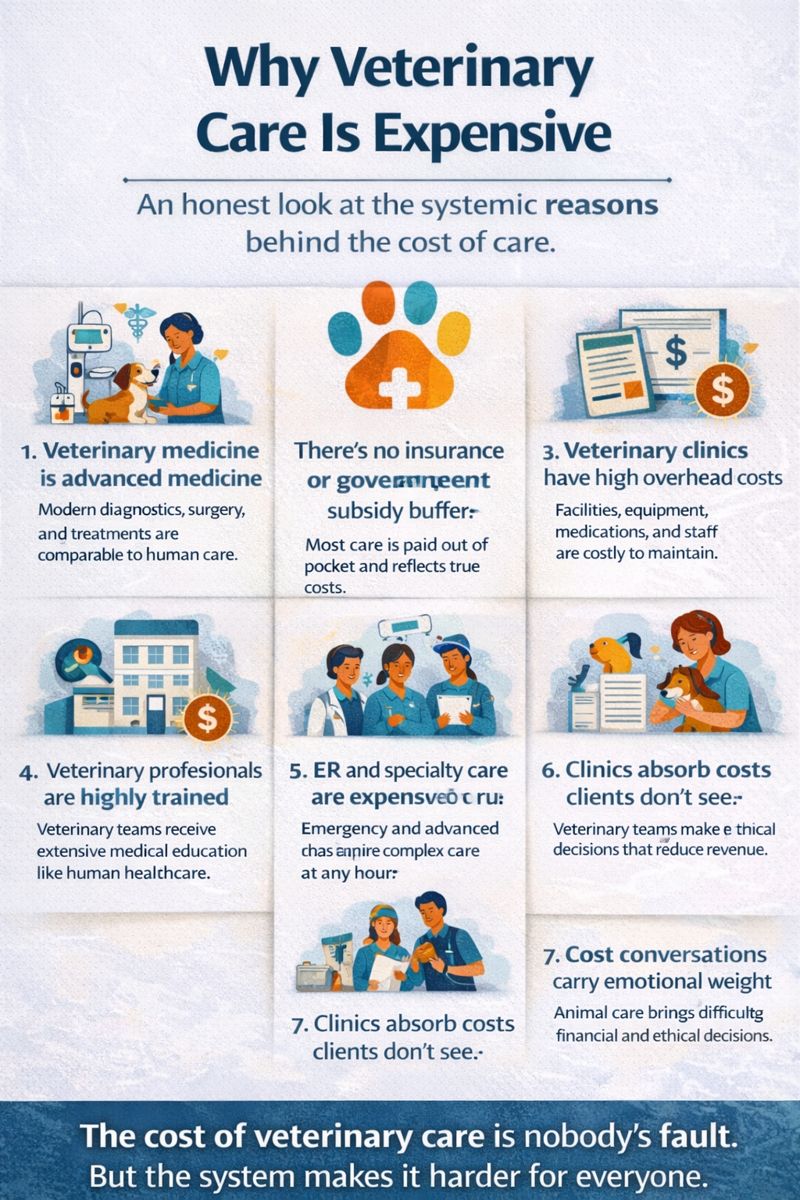

Few topics create as much tension in veterinary medicine as cost.

Clients feel shocked and overwhelmed.

Veterinary teams feel blamed and misunderstood.

Conversations become emotionally charged on both sides of the exam table.

To understand why veterinary care is expensive, we have to move beyond emotion and look at how the system is designed.

The reality is this:

Veterinary medicine is expensive because it delivers high-level medical care in a system that receives none of the financial protections human healthcare does.

1. Veterinary Medicine Is Modern Medicine

Veterinary care today looks very different from what it did even 20–30 years ago.

Modern veterinary clinics provide:

- Advanced diagnostics (digital radiology, ultrasound, in-house labs)

- Surgical procedures comparable to human outpatient surgery

- Anesthesia and pain management protocols

- Emergency and critical care

- Ongoing chronic disease management

- Highly trained clinical teams

These services require:

- Specialized equipment

- Continuous maintenance and calibration

- Ongoing training and certification

- Strict medical and legal standards

High-quality medicine costs money—whether it’s for humans or animals.

2. There Is No Insurance or Government Subsidy Buffer

One of the biggest differences between human and veterinary medicine is who pays the bill.

In human healthcare:

- Costs are spread across insurance pools

- Government programs subsidize care

- Hospitals absorb losses through large systems

In veterinary medicine:

- Most care is paid out of pocket

- Pet insurance penetration remains low (estimated under 5% in the U.S.)

- Clinics must charge the full cost of care to stay operational

This means veterinary invoices reflect the true cost of care, not a discounted or subsidized version (AVMA, 2023).

3. Veterinary Clinics Have High Overhead Costs

Running a veterinary clinic is expensive, even before a single patient is seen.

Common overhead costs include:

- Medical equipment and maintenance

- Medications and controlled substances

- Laboratory supplies

- Facility costs (rent, utilities, compliance)

- IT systems and medical records

- Regulatory and legal compliance

- Insurance (liability, workers’ compensation)

According to the American Veterinary Medical Association, overhead can consume 60–70% of clinic revenue, leaving a much smaller margin than many clients assume (AVMA, 2022).

4. Veterinary Professionals Are Highly Trained (and Underpaid)

Veterinary teams are not “unskilled labor.”

They include:

- Veterinarians with doctoral-level education

- Credentialed veterinary technicians

- Trained assistants and support staff

- Client service professionals managing complex emotional interactions

Veterinarians graduate with some of the highest debt-to-income ratios in healthcare, while earning significantly less than physicians (AAVMC, 2022).

Despite this:

- Clinics struggle to retain staff

- Wages are rising out of necessity, not excess

- Burnout and turnover are widespread

Paying people fairly is not what makes veterinary medicine expensive.

Not paying them fairly makes it unsustainable.

5. Emergency and Specialty Care Add Significant Cost

Emergency and specialty veterinary care operate under unique pressures.

These clinics must:

- Staff 24/7 or extended hours

- Maintain specialized equipment

- Employ advanced training

- Handle high-acuity, emotionally intense cases

These services cost more for the same reason human ER care costs more: availability, acuity, and complexity.

The difference is that veterinary ER costs are paid directly by the client at the time of care.

6. Veterinary Clinics Absorb More Cost Than Clients Realize

Contrary to popular belief, clinics often:

- Discount services

- Write off unpaid balances

- Absorb losses on complex cases

- Spend uncompensated time educating clients

Veterinary teams routinely make ethical decisions that reduce revenue to prioritize patient welfare.

These choices do not appear on invoices—but they do affect sustainability.

7. The Emotional Cost Is Real Too

Cost conversations are emotionally heavy.

Veterinary teams routinely navigate:

- Financial limitations

- Client guilt and grief

- Ethical dilemmas

- Accusations of profiteering

This emotional labor is rarely acknowledged and contributes to burnout, compassion fatigue, and moral distress (Bartram & Baldwin, 2010).

When cost is framed as greed rather than reality, trust erodes on both sides.

The Bigger Picture

Veterinary medicine is expensive because:

- It delivers modern medical care

- It operates without subsidies

- It carries high overhead

- It relies on highly trained professionals

- It absorbs ethical and emotional labor daily

This does not mean care is inaccessible by design.

It means the system is fragile.

Improving affordability requires system-level solutions, not blame:

- Expanded pet insurance education

- Preventive care planning

- Transparent cost communication

- Realistic expectations about medical care

The Takeaway

Veterinary medicine is not expensive because clinics are greedy.

It is expensive because it provides advanced medical care in a system that asks clients and clinics to carry the full cost alone.

Understanding this reality doesn’t erase the difficulty of paying for care—but it can restore empathy to conversations that matter deeply to everyone involved.

Reflection Question

What would change if we talked about the cost of veterinary care as a systems issue rather than a moral one?

References (APA)

American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges (AAVMC). (2022). Annual data report. https://www.aavmc.org

American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). (2022). Veterinary economics reports. https://www.avma.org

American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). (2023). Pet insurance and the cost of care. https://www.avma.org

Bartram, D. J., & Baldwin, D. S. (2010). Veterinary surgeons and suicide: A structured review of possible influences on increased risk. Veterinary Record, 166(13), 388–397. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.b4794

Leave a comment