Lean Six Sigma is often misunderstood in veterinary medicine.

It’s frequently associated with manufacturing, rigid productivity metrics, and pressure to do more with fewer people. In a profession built on care, ethics, and emotional labor, that association can feel deeply misaligned.

But Lean Six Sigma, when applied correctly, is not about squeezing people.

It is about removing unnecessary friction from systems so teams can provide care without constant strain.

What Lean Six Sigma Actually Is

Lean Six Sigma combines two complementary approaches:

- Lean focuses on eliminating waste, redundancy, and unnecessary steps

- Six Sigma focuses on reducing variation and errors through reliable processes

The goal is not speed alone.

The goal is clarity, consistency, and safety.

In healthcare settings, Lean Six Sigma has been shown to improve workflow efficiency, reduce errors, and lower staff stress when applied thoughtfully and ethically (DelliFraine et al., 2014; Holden, 2011).

Why Veterinary Medicine Is Ripe for Systems Improvement

Veterinary teams often experience stress not because they lack skill or commitment, but because systems add unnecessary complexity.

Common pain points include:

- Inconsistent intake processes

- Poor handoffs between roles

- Redundant documentation

- Unclear task ownership

- Bottlenecks that trigger chaos during peak hours

These inefficiencies increase cognitive load, emotional labor, and error risk, particularly under time pressure.

Lean Six Sigma helps identify where work is harder than it needs to be.

Where Lean Thinking Helps Most in Vet Med

Lean begins with one core question:

Which steps add value to patient care, and which steps add burden without benefit?

In veterinary medicine, Lean thinking can:

- Clarify workflows so teams aren’t constantly improvising

- Reduce decision fatigue during busy periods

- Improve communication across roles

- Decrease client frustration by creating predictable processes

Importantly, Lean protects professional judgment by removing unnecessary noise around it.

Six Sigma and Error Reduction in Clinical Care

Six Sigma focuses on reducing variation that increases risk.

In veterinary clinics, variation often appears as:

- Different medication prep methods

- Inconsistent anesthesia protocols

- Variable discharge instructions

- Uneven training across shifts

Research shows that standardization of routine clinical processes reduces error rates and improves safety in healthcare environments (Pronovost et al., 2006).

This does not eliminate autonomy.

It creates reliable defaults so clinicians can focus on complex decision-making.

Emotional Labor and Inefficient Systems

Inefficiency does more than waste time.

It increases emotional labor.

When systems fail, teams absorb:

- Client frustration

- Team conflict

- Moral distress from rushed care

- Anxiety about mistakes

Emotional labor is strongly associated with burnout when it is chronic and unsupported (Grandey & Gabriel, 2015).

Reducing inefficiency is not just operational.

It is psychological harm reduction.

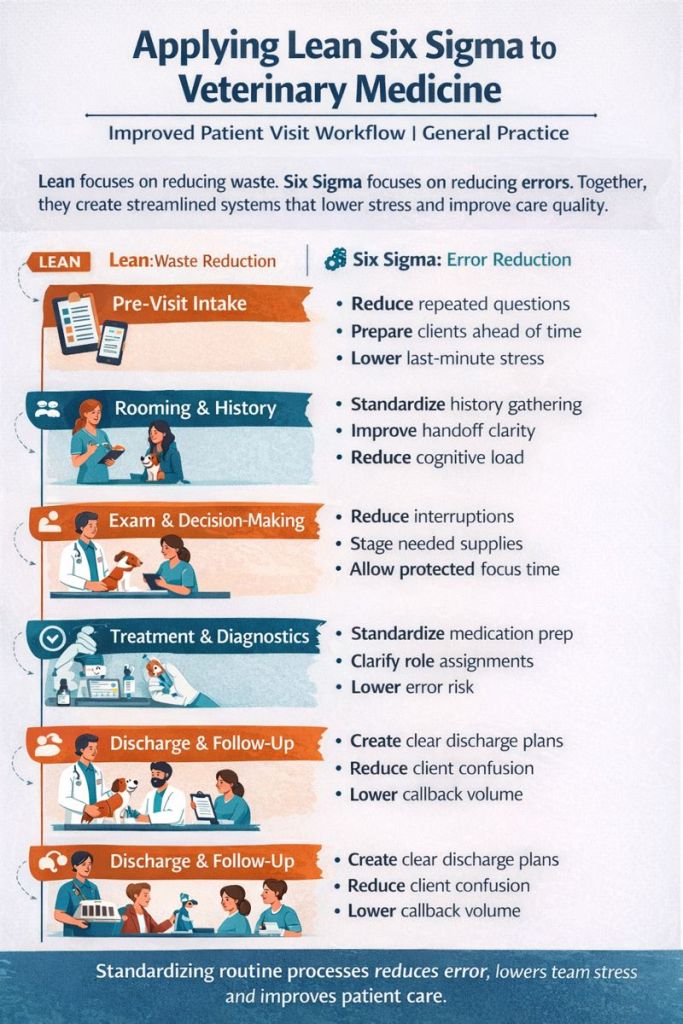

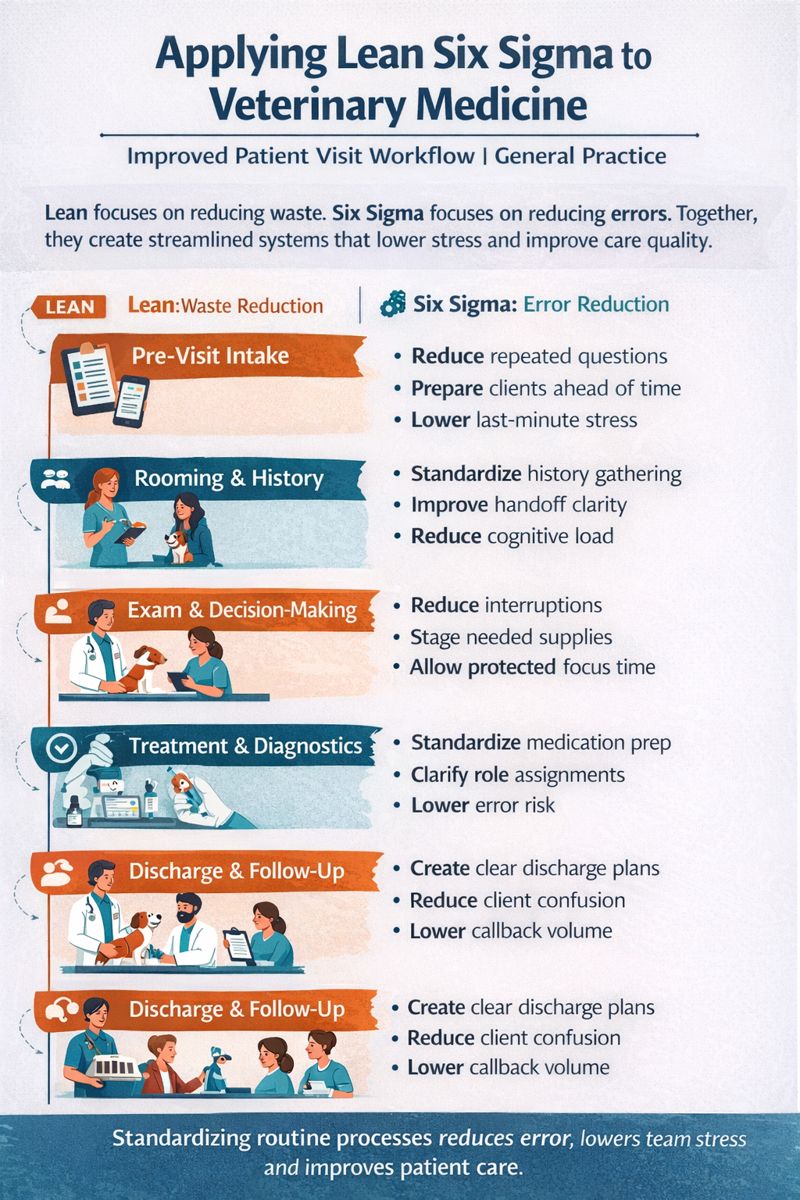

Sample Lean Six Sigma Workflow: General Practice Veterinary Clinic

Below is an example of how Lean principles can be applied to a routine wellness + sick visit workflow.

Before: Common Pain Points

- Client arrives without clear intake expectations

- Technician gathers history multiple times

- Veterinarian interrupted repeatedly during exam

- Missing supplies delay diagnostics

- Discharge instructions rushed or inconsistent

Result:

- Increased stress

- Longer appointments

- Frustrated clients

- Team tension

After: Lean-Informed Workflow Design

1. Pre-Visit Intake (Lean: Waste Reduction)

Design changes

- Standardized digital intake form completed before arrival

- Clear appointment type selection (wellness vs sick vs recheck)

- Automated reminders outlining what to expect

Impact

- Reduces repeated questioning

- Improves appointment preparedness

- Lowers client anxiety

2. Rooming & History (Lean + Six Sigma)

Design changes

- Technician follows a standardized history checklist

- Information documented in one location

- Clear criteria for escalation or diagnostics

Impact

- Reduces variation

- Improves handoff quality

- Lowers cognitive load

3. Exam & Decision-Making (Lean: Protecting Value-Added Work)

Design changes

- Veterinarian protected from interruptions during exam

- Technician assigned as primary support

- Supplies pre-staged for common diagnostics

Impact

- Improves focus

- Reduces delays

- Enhances care quality

4. Treatment & Diagnostics (Six Sigma: Error Reduction)

Design changes

- Standardized medication prep and labeling

- Checklists for anesthesia and procedures

- Clear role assignments during treatment

Impact

- Reduces errors

- Improves team coordination

- Builds trust

5. Discharge & Follow-Up (Lean: Flow + Clarity)

Design changes

- Standard discharge templates customized per case

- Written and verbal instructions aligned

- Clear follow-up plan communicated

Impact

- Reduces client confusion

- Lowers callback volume

- Improves adherence

What Changed?

Not the people.

The system.

By removing redundancy, clarifying roles, and standardizing routine steps, the clinic reduced stress without increasing speed or caseload.

What Lean Six Sigma Should NOT Do in Vet Med

Lean Six Sigma should never be used to:

- Increase appointment volume without support

- Justify understaffing

- Eliminate recovery time

- Measure productivity without context

When efficiency is used without regard for human limits, burnout increases. That is not Lean. It is a misuse.

The Takeaway

Lean Six Sigma, when applied ethically, is not about doing more with less.

It is about doing meaningful work with less friction, less confusion, and less harm.

Veterinary medicine doesn’t need industrial thinking.

It needs humane systems thinking.

Reflection Question for Leaders

Where might inefficient processes be increasing stress and emotional labor for your team without improving care?

References (APA)

DelliFraine, J. L., Langabeer, J. R., & Nembhard, I. M. (2014). Assessing the evidence of Six Sigma and Lean in the health care industry. Quality Management in Health Care, 23(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1097/QMH.0000000000000004

Grandey, A. A., & Gabriel, A. S. (2015). Emotional labor at a crossroads. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2, 323–349. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111400

Holden, R. J. (2011). Lean thinking in emergency departments. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 57(3), 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.08.001

Pronovost, P., Needham, D., Berenholtz, S., et al. (2006). An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections. New England Journal of Medicine, 355(26), 2725–2732. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa061115

Leave a comment